The Consigliere to The PayPal Mafia: And The Path to It

- BizzNeeti

- Jan 27, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Feb 5, 2020

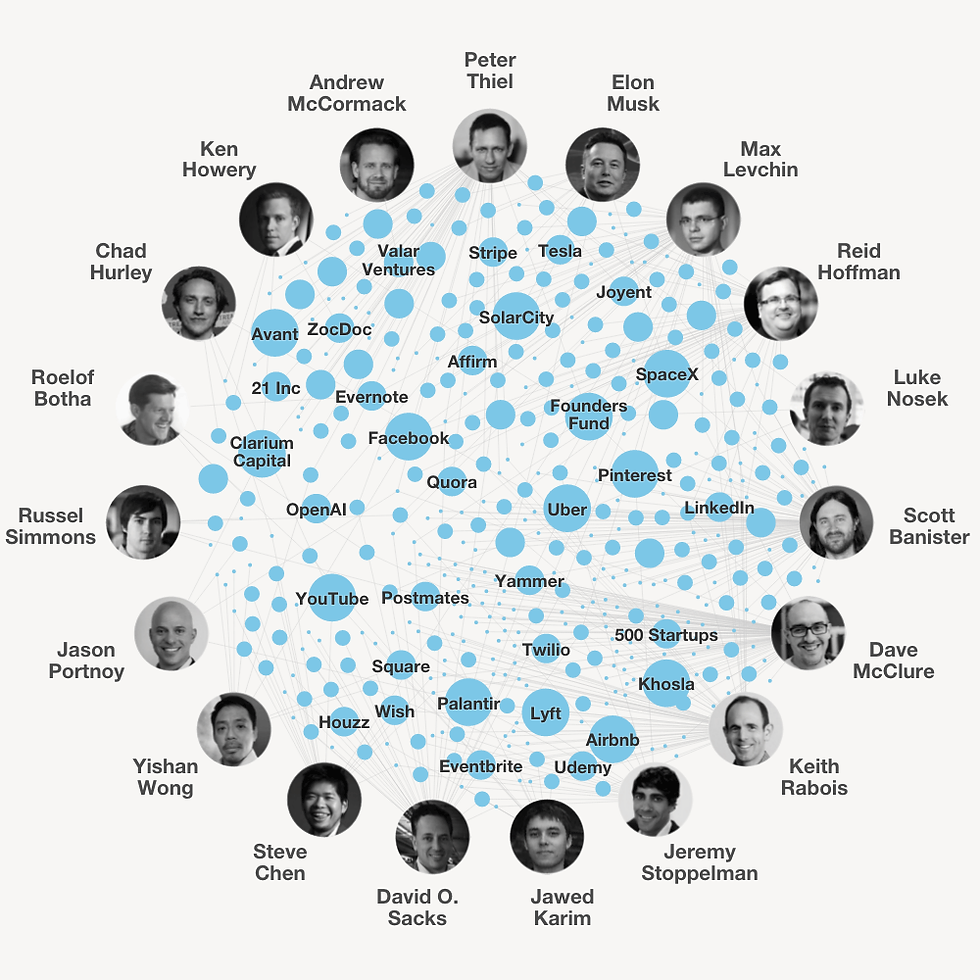

The PayPal Mafia is huge, and its alumni so successful. The words alumni and mafia never feature in the same sentence. But then, the alumni of the PayPal mafia are not ordinary people who can be referred to with ordinary sentences. Their careers and success stories didn’t stop at PayPal, and they went on to build some of the most recognizable digital brands today.

Indeed, there was a time when every engineer in America dreamt of minting some millions off the Internet, and there were quite a few who actually did. But every start-up has a story, of how it was built, what hardships it had to face during its early and growth stages and how finally they went on to build winner products and services.

In the second of this four-part series, let’s head on and take a look at Elon Musk’s digital ventures, including his very first company Zip2, and the subsequent online financial services company X.com.

…

A quick search on the URL x.com leads us to a blank, white webpage with just a symbol “x” on the top-left corner. Musk actually bought this URL from PayPal, for safekeeping as a memory of his company X.com. This might come across as a very geeky move, but Elon Musk was the geek to be.

…

Having enrolled at Stanford for a degree in Physics, Musk went for a road trip in a beat-up BMW a couple of decades old. Along with his brother, Kimbal Musk, he started brainstorming the idea of an internet company, since it was just the start of the famed ‘dotcom bubble’, and Musk was convinced this was the way to success. Having returned with an idea for an online network for doctors, Musk went back to start at Stanford while Kimbal worked up the “business plan and the sales and marketing side of it, but it didn’t fly”.

After just two days at class, Elon decided to defer his admission and told his Dean that he wanted to start his own internet company, and he might be back after failing within six months. The Dean, almost preposterously disagreed, and has never heard from Musk since.

The first inklings of a viable Internet business had come to Musk during his internships. A salesperson from the Yellow Pages had come into one of the start-up offices. He tried to sell the idea of an online listing to complement the regular listing a company would have in the big, fat Yellow Pages book. The salesman struggled with his pitch and clearly had little grasp of what the Internet actually was or how someone would find a business on it.

The flimsy pitch got Musk thinking, and he reached out to Kimbal, talking up the idea of helping businesses get online for the first time. “Elon said, ‘These guys don’t know what they are talking about. Maybe this is something we can do,’” Kimbal recounts. This was 1995, and the brothers were about to form Global Link Information Network, a start-up that would eventually be renamed Zip2.

It was a time when the internet had just started out, and it was easy to look for services that a person would heavily use in the physical world, but had no corresponding digital options.

Pitching an already hit service combined with the ease of at-home and on-demand access would guarantee a good fraction of innovators and early adopters, and that would probably be enough to garner the attention of the early majority given the boom internet usage enjoyed.

The Zip2 idea was ingenious. Essentially, Musk set out to give everyone a shot at finding pizza easily, giving them the location of their closest pizza parlor and the turn-by-turn directions to get there.

Few small businesses in 1995 understood the ramifications of the Internet. They had little idea how to get on it and didn’t really see value in creating a website for their business or even in having a Yellow Pages-like listing online. Musk and his brother hoped to convince restaurants, clothing shops, hairdressers, and the like that the time had come for them to make their presence known to the Web-surfing public.

Zip2 would create a searchable directory of businesses and tie it into maps. This may seem obvious today—think Yelp meets Google Maps—but back then, not even stoners had dreamed up such a service.

He bought a disk with a digital database of listings, and convinced a digital mapping company to lend their software to him. While low sales pulled them down, Musk’s relentless hours at coding, bringing continuous improvements to the software kept them hoping.

The brothers resorted to bootstrapping for the early stage. From renting out a studio apartment-sized office, barely being able to afford any furniture, owning just a single computer with a dial-up connection to the internet to having four budget meals a day, showering at the YMCA and coding only at night so that the website remains up and running during the day, the pair endured a lot of hardships for their venture to see the light of success.

Musk traded place to live for an intern, had a very meagre sales force, with just a two-by-two job listing reading “Internet Sales Apply Here”. Although there was little success initially, he kept his sales team motivated. The company gained their first big dollars from auto-dealers when they finally hired a professional sales guy. That was the beginning of the boom for Zip2.

Musk has always been one person who likes to go all-out with his marketing and PR. Early glimpses were seen when he, having finally secured a real chance at being funded by investors, encased his computer in a huge box, and put it up on wheels, giving an air that his website was being run out of a mini-supercomputer.

This, combined with a look onto Elon’s undying efforts and his zeal and drive to succeed prompted venture capital firm Mohr Davidow to infuse the firm with an investment of US$ 3 million in 1996. Musk traded the CEO chair and settled with being the CTO instead. He had no problems being the CTO as long as the newly installed CEO Rich Sorkin was making the product better and the company was headed in the direction Musk wanted it to.

However, the days of harmony were few and sparse, with Musk often clashing with formal software engineers hired and the way the company was being handled.

While the new software engineers wrote code in chunks and required a fraction of number of lines of code to accomplish the same tasks as Musk, he claimed his code worked much faster and with greater efficiency. They called his code a hairball, he claimed the hairball worked better.

No doubt, Rich gave the product a new direction, which was indeed working well, earning huge revenue selling software packages to newspapers and media companies like The New York Times, Knight Ridder and Hearst Corporation to enable them come online after missing the early adopter period of the internet by creating their own online versions of directories for classifieds, jobs and other listings.

The success was such that Zip2 trademarked the tagline “We power the press”.

However, Musk believed that the company would have been better off targeting consumers directly, and did not agree with the upcoming merger with CitySearch, a competitor firm playing at the national level. He staged a coup, got Rich ousted as CEO and from the Board, and got a VC as CEO instead. The new CEO quickly sold the company off to Compaq for US$ 307 million, making a huge return on initial investment.

Zip2 was briefly used to supplement local search results for AltaVista, and remained just a feature on the now defunct pioneer of search.

…

When Musk was certain that Mohr Davidow was looking for an exit and the board had decided to sell Zip2 and had started looking for suitable buyers, Musk to decided to move onto his next venture, having learnt a few hard lessons from Zip2. He started chatting up current staff at Zip2 to see if someone was interested enough to work with Musk post-Zip2.

By the time the Compaq deal took off and left Musk richer by US$ 22 million, he was ready with a new team comprising of a former Zip2 executive and two bankers from his internship at Bank of Nova Scotia in Canada.

While the Silicon Valley trend was to win big with an internet venture and stash away your new found wealth while you use your credentials to seek funding for your next venture, Musk invested most of his savings in his next company X.com.

X.com was meant to be a full-fledged online bank at a time when people were not even comfortable with the idea of buying books online.

Musk and his new company was laughed at multiple times. The banking system too came up only due to the unreliable security of the internet at that time, which derailed the initial idea of a simple online payments provider. Moreover, the banking industry, as Musk found out, was heavily regulated and had huge barriers to entry. The list of problems even before the company took formidable flight was not limited to this. Months after getting some work, thought and team together, he had a quarrel which saw a coup initiated against him and resulted in more than half of the engineers and all co-founders except Musk leave the firm to start out on their own.

Musk was somehow able to gather funding from Sequoia Capital and hire a few smart engineers from Silicon Valley with his rah-rah speeches about the future of Internet Banking. The company secured a banking license and a mutual fund license and formed a partnership with Barclays.

X.com’s small software team had created one of the world’s first online banks complete with FDIC insurance to back the bank accounts and three mutual funds for investors to choose.

Musk gave the engineers $100,000 of his own money to conduct their testing. On the night before Thanksgiving in 1999, X.com went live to the public. “I was there until two A.M.,” Anderson, an employee, said. “Then, I went home to cook Thanksgiving dinner. Elon called me a few hours later and asked me to come into the office to relieve some of the other engineers. Elon stayed there forty-eight hours straight, making sure things worked.”

Under Musk’s direction, X.com tried out some radical banking concepts. Customers received a $20 cash card just for signing up to use the service and a $10 card for every new person they referred. Musk did away with niggling fees and overdraft penalties. In a very modern twist, X.com also built a person-to-person payment system in which you could send someone money just by plugging their email address into the site.

The idea was to create a kind of agile bank account where you could move money around with a couple of clicks on a mouse or an e-mail. This was revolutionary stuff, and more than 200,000 people bought into it and signed up for X.com within the first couple of months of operation.

Soon enough, Musk had competition from Confinity, who rented their office space - a glorified broom closet - from X.com and were trying to make it possible for owners of Palm Pilot handhelds to swap money via the infrared ports on the devices.

Between X.com and Confinity, the small office on University Avenue had turned into the frenzied epicenter of the Internet finance revolution. “It was this mass of adolescent men that worked so hard,” Ankenbrandt said. “It stunk so badly in there. I can still smell it—leftover pizza, body odor, and sweat.”

However, this soon turned into war when Confinity launched their email-based payments service PayPal, resulted in huge dollars being spent by both trying to gain market share faster than the other. The war ended up with the two companies being merged and Musk retaining the CEO chair and the company name X.com. Shortly after the deal closed, X.com raised $100 million from backers including Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs and boasted that it had more than one million customers.

This happy period, however, didn’t last long, with internal mini-battles erupting due to complete mismatch of cultures between Confinity and X.com. While employees of the former wanted to focus on the PayPal service, Musk and his faction championed the X.com brand. A programmer’s war broke out in the merged company when Peter Thiel led-Confinity faction wanted to use open-source platforms such as the Linux software and the Musk-led faction preferred Microsoft’s data-center software as being more likely to keep productivity high. There were issues with continuous explosion of users that led to rising levels of fraud and piling on of fees from banks and credit card companies.

Two months after the companies merged, and Musk was on a honeymoon trip to Australia, a coup was staged by Peter Thiel and Musk lost control of yet another venture of his. He agreed to remain an advisor to the firm, and maintained that he was cool with Peter Thiel leading the firm as long as their vision and direction for the company coincided, though this version was heavily contested by others at the firm at that time.

Though, by 2001, the company was rebranded as PayPal, and Musk’s influence in the company was fading, he kept investing further and became the largest shareholder and contrary to most people’s expectations, was quite supportive of Peter. The board wanted to sell and exit as the dotcom bubble burst, but Musk along with another board member convinced the rest to stay and hold out for a better offer since they were clocking revenues of US$ 240 million despite the bubble burst. The holding out finally paid off when eBay bought PayPal for US$1.5 billion, leaving Musk richer by US$180 million after taxes.

…

There are quite a few observations we can take away from the way these companies were born and finally grew to see success.

Both these ventures are classic examples of how an entrepreneur saw a space of opportunity and was willing to look for the perfect use and wait for it to be developed before taking any steps and advances in haste.

Innovation might be simple enough and you need not develop an entirely novel, cutting edge product as long as one is able to find a good solution fit for a problem that has largely been unaddressed or can be addressed in a radically better manner, there need not be huge innovation involved.

For example, Services like Dollar Shave Club, Pillow.com don’t offer anything radically new but solve some very commonplace problems with such elan.

No amount of marketing effort can beat the good old trick of having a useful product that adds value, but it just might take you places if you have hit the right formula.

Bootstrapping and holding out and being frugal and inventive are gems of qualities that one might need in his arsenal to rise to cult status in his entrepreneurial journey. Needing your company to be funded is inevitable but there might arise a conflict in the definitions of success for the parties involved.

The firm at any point in time may work to fulfill the dream of his founder, or serve its customers in the best possible manner. Or it might be able to figure out a middle path.

Handling issues diplomatically while also helping your vision prevail in the long run is more important an art than the art of war or art of living itself.

It is quite possible for entrepreneurs to be developing something, but find a good product in the process of developing something entirely else. We have seen how Musk had set out to develop a Yelp+Maps product but the company doled out software packages for newspapers that were a hit in the market. From aiming to help people find a pizza parlour, Zip2 went on to “Power the Press”!

A modern-day entrepreneur might just learn enough from these episodes, along with the all-important lesson of grit and determination and the consistent labor ultimately required along with an actually good and sellable product.

Comments