When Capitalism Tries to Save the World: Impact Investing

- BizzNeeti

- Aug 26, 2020

- 8 min read

On running a simple Google Image Search for the query "impact investing", somewhat controlling for location and personalized search, we received seven of the first sixteen image results with some illustrations of trees and planet Earth, while all others were flowcharts and matrices, all mentioning philanthropy/grant support.

For an idea that was first coined thirteen years ago in 2007, by the illustrious and influential Rockefeller Foundation. This niche industry boasts of assets under management (AUM) of $715 Bn globally in 2020, a significant increase from $502 Bn in 2019, it looks like Impact Investing still has a long way to go before it can be compared with mainstream PE/VC investing. Head to head, global PE AUM crossed $4 Tr in 2019, and is expected to touch the $5 Tr mark by 2022.

…

Now that we know what Impact Investing probably is not, what is it after all? Michael Drexler and Abigail Noble of the World Economic Forum define Impact Investing as “an investment approach intentionally seeking to create both financial return and positive social impact that is actively measured”. That is, you have to intend to do good, and you have to measure whether you’re succeeding.

Now, according to this definition, there might exist two possible extremes on the spectrum, when the investee founder might say:

“Trust me. Trust me. I’m a good guy. I have good intentions — and I’m going to destroy your money.” This can’t really be called investing, this is more like giving a grant support, more of philanthropy, with guarantee only on money being spent, but not return produced. In extreme cases, there might not even be a very high chance of the money actually creating measurable positive impact on the society.

“I have no intentions but look I’ve created jobs, ex post” That is the post-rationalization of an economics-only business model. This is just another investment made, and while this kind of a business seems to be poised to hold good on its promise of a return for the investors, there is a very low chance of any kind of social impact being created.

We see both of these things in the marketplace, and we think this confusion at the meta level really hurts the sector.

To us, the key about intentionality is that it must focus on a business model, a business plan upfront, with both economic and social impact. It’s “I tell you what I will do, how I’ll do it, and you can hold me accountable.” Once you have the intentions, once you track impact this way, whether you’re a bottom-of-the pyramid business, whether you are looking at sustainable agriculture or renewable energy, it’s totally open.

…

Investing is all about catching early trends. And everyone agrees Impact is one area with not only enormous growth potential from the business’ side, but also from the consumers’ side, who want to be seen as being associated with sustainable brands, with socially responsible value chains.

But despite this growing interest, impact investing still faces a significant stumbling block that limits the flow of new capital into the field: not everyone agrees on what “impact investing” actually means.

Currently, impact can mean anything from venture investments in new health technologies to microfinance loans in Peru; from affordable housing in the US to renewable energy in India; from social impact bonds to private equity funds that create jobs. That’s just the beginning of the confusion—even if you accepted that such diverse investments should all be grouped into one category, how do you even measure and compare impact anyway?

While ‘new trends’ is what all investors like, uncertainty is what all investors are most wary of. This uncertainty of purpose and measurement of its achievement has led most investors to either of these three buckets, in terms of impact:

Search for examples of impact in their existing portfolios, freeing them up from having to allocate funds separately for impact, and hence eliminating any incremental capital.

Setting aside small, experimental funds, trying to learn or achieve very specific objectives

Do not participate

Either of these three buckets are not giving any advantage to impact investing, and it still remains a niche area of interest. It needs systemization in terms of selecting the right investee and then measuring the success and weighing in returns on the investments made.

Impact investors must evaluate any potential investee on these three guiding principles:

1. Type of impact

Each investor will have their own conception of the social good they are trying to achieve. The investor might want to fund the invention of new solutions or she might simply want to improve the practices of existing businesses. There is no right or wrong impact class—what matters is identifying preferences. This might be classified across five categories:

Place: Investments in companies or projects that are located in a particular place (or benefit particular group of people). A good example would be Selco, a company rendering sustainable energy sources to rural regions of the country. The focus has been concentrated on rural Karnataka, with the company launching the first rural solar financing program in India, having already contributed over 120,000 installations.

Process: Investments that pay careful attention to business practices, such as “fair trade” coffee, equitable labor practices in a supply chain or buy-one-give-one models that provide access to goods and services to those in need. Consider Pipal Tree for example, a company that aims to train rural youth and get them sustainable jobs. With an expertise in construction, this company even has trained all-female crews, one of which, possibly the first-of-its-kind in India, erected 10 large warehouses all by itself on this vast site in Sonbhadra district of Uttar Pradesh back in 2015-16.

Planet: Investments that have a clear and measurable environmental benefit, either through the preservation and restoration of critical natural habitat, or the measurable reduction of carbon dioxide through new energy efficient products. Consider Waste Ventures India, a startup launched back in 2011, averts up to 90% of waste from dumpsites and produces nutrient-rich organic compost. They sign multi-year contracts with local municipalities and employ waste pickers at their processing units to segregate waste.

Product: Investments in products or services that have positive social benefits. Ashoka Changemakers, an open-ended platform for social innovation that was one-of-its-kind in the world, aims to revive the craftsmanship and talent that is unharnessed in rural India and aims to provide them with their deserving recognition. They started the Rangmanch retail chain under FabIndia which proved to be a huge success.

Paradigms: Investments that attempt to change an entire system for the better. Consider Arth, a social impact startup. Launched in 2015, the venture delivers credit for small and micro-entrepreneurs, and provides livelihood welfare services with a focus on financing rural women micro- entrepreneurs and micro-merchants.

2. Intensity and Immediacy of Impact

Having identified what kind of impact the investor seeks, the second question is to understand the intensity and scope of the desired impact, for which category of beneficiaries the impact is targeted, and over what timeframe.

Might be something long-term critical change like Aravind Eye Care Hospitals which aims to eliminate needless blindness by sponsoring 50% of their treatments and surgeries, or something small and incremental like Toppr launching its Toppr OS, a platform to digitally blend in-school and after-school learning.

3. Impact Risk Profile

With every impact investment there is not only financial risk, but also impact risk: will the desired impact be delivered? Investors should ask what existing evidence they need to see before they make the investment, or what metrics they will expect to see after the investment has been made that can demonstrate progress. Consider the example of Sulabh Sanitation Mission Foundation, which aims to create an enabling environment against the unhygienic practices that are prevalent in India. With its parent organization, it might be easy to evaluate its own performance, but it might be very difficult to measure the overall change it has been able to bring about.

…

This brings us to probably the most important question: How does one measure impact?

Although the business world has universally accepted tools for estimating a potential investment’s financial yields, no analogue exists for evaluating hoped-for social and environmental rewards in dollar terms.

The Rise Fund and the Bridgespan Group have developed a methodology for estimating the financial value of the social or environmental good generated by impact investments. The six-step process culminates in a number—called the impact multiple of money, or IMM—that expresses social value as a multiple of the investment.

Assess the relevance and scale

Identify target social or environmental outcomes

Estimate the economic value of those outcomes to society

Adjust for risks

Estimate terminal value

Calculate social return on every dollar spent

Given such a structure lets you measure the social return on your investment, what exactly do you look at while making an investment decision? Omidyar Network highlights four key tenets to follow from their lessons learned in eight years of impact investing:

Problem first, structure second

Talent is key

Human capital contributions often exceed the value of financial contributions

Match return expectations to the market you are looking at

…

A research paper titled Impact Investing, by Brad M. Barber, Adair Morse and Ayako Yasuda published in the Journal of Financial Economics, whose goal was to understand whether investors are willing to accept lower financial returns for nonpecuniary benefits of intentional impact investing, shows that ex-post financial returns earned by impact funds are 4.7 percent points lower than those earned by traditional VC funds, even after controlling for a host of fund characteristics.

It also found that on average, impact investors are willing to forego 13 to 18 percentile ranks of vintage-geography benchmarked performance or about 2.5 to 3.7 percent points in expected excess IRR.

Does this mean businesses that are focused on creating a positive social impact are less competitive and profitable? There are certainly examples where impact investment has been successful at generating both a commercial return and a positive impact. But there are also those who argue there is a trade-off between profitability and impact.

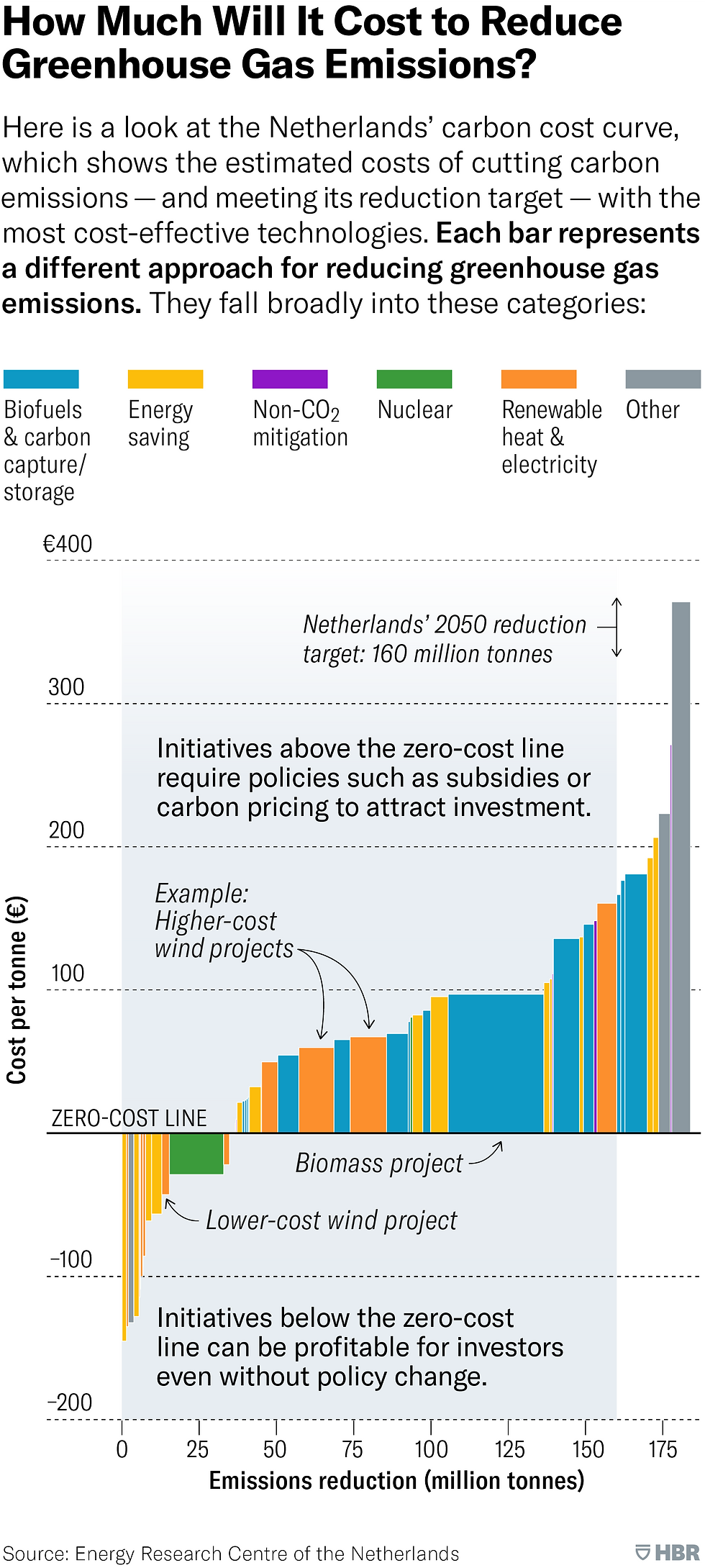

But who is right? The answer is both. An easy way to clarify the issue is by looking at a typical “carbon cost curve”, which shows the financial costs of investments that would reduce carbon emissions.

The key insight is: If there really were no trade-off between profit and impact, then cost-curves for all these problems would be made up solely of investments “below the line” all the way along. If this were the case, then we wouldn’t need impact investors. Regular investors would already be investing in solving climate change, removing plastic from the oceans, and educating the world’s women.

Businesses must seek profits given the less profitable will tend to be muscled-out by the more profitable over time. Under today’s rules, some harmful investments offer inflated profits because investors don’t have to pay for the damage they cause through, for example, carbon emissions or the health impacts of air pollution. Meanwhile, many worthy investments are unprofitable because investors are not rewarded for their associated benefits, such as improvements to health by reducing air pollution.

To bring about Sir Ron Cohen’s revolution, in which investment “does not require reducing profits in favor of impact,” our only choice is to change these rules. We already know what we must do: “Lift the zero-cost line” with carbon pricing, subsidies, or regulations, so that more actions fall below it and attract investment.

In other words, once externalities have been internalized, then all investing becomes impact investing.

This calls for identifying opportunities that have already fallen below the zero-cost line, rallying behind the required changes in policy and encouraging philanthropists to aim higher. A grant is a one-time help, and the money is gone, irrespective of the success of the objective, however, with investing, the money ideally comes back to you, multiplied, so you can do more good!

…

Over the next four decades the millennials are going to inherit some $40 trillion. Thirty-six percent of them think that the primary purpose of business should be to improve society and about half of millennials — millennials are people born between 1980 and 2000 — think that businesses can do more around resource scarcity and inequality.

It’s not going to be that all investing is impact investing, but a lot more investment decisions will have considerations about impact and the transparency and accountability that comes with technology and social media is going to propel that. It will get harder and harder for mainstream investors to not develop some strategies in this area.

Comments